IV. The end of the community

The other Monastirians, also becoming teachers of the Alliance, constituted a model for new generations of their Hometown, where they spent at least their summer holidays. The social ascension of the Graciani brothers, Léon and Elie, deserves some attention. Besides this symbolic dimension, the attachment to the city of origin was so strong that some of them were actively involved in the affairs of the community of Monastir. Such is the case of Isaac Perez concerning the teaching of Turkish in the schools of this city.

- Emigration to the New World

A side from the organized emigration by the AIU into the New World, the Jewish populations of Macedonia experienced the phenomenon of emigration to America, notably to the United States, by the end of 1906. The first wave of Jewish emigration of Monastir, remained limited and seemed to have a rather individual character in spite of the fact that Mr. Arié took initiative to teach English at the school building in winter 1907, date in which the number of emigrated Jews oscillated between 30 and 40 persons each week. The wave slowed down because of unfavorable weather conditions, but this allowed families to take advantage of the winter period to learn English and prepare.

Security was the main reason for departure of the Jews: all of Macedonia was shaken by the insurrections between Bulgarian and Greek groups at the beginning of the 20th century. Then, the obligation of military service for the non-Muslim elements of the Ottoman Empire following the Young Turkish Revolution also caused further abandonment of the city. Still, the war situation was not the only reason of this matter: rumors of success among emigrants in the New World arouse a strong interest for those who remained. The case of Léon Graciani is emblematic: in the footsteps of his older brother Elie, Léon also applies for a job in the JCA schools in Argentina in the hope of making sufficient savings to make his parents have a better life. When the time came to leave for Argentina, he was stuck in Monastir due to the outbreak of the Balkan war in 1912 and gave up a year later during his post in Morocco.

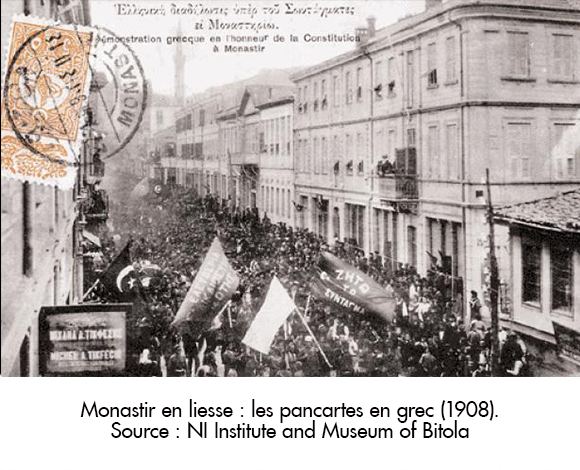

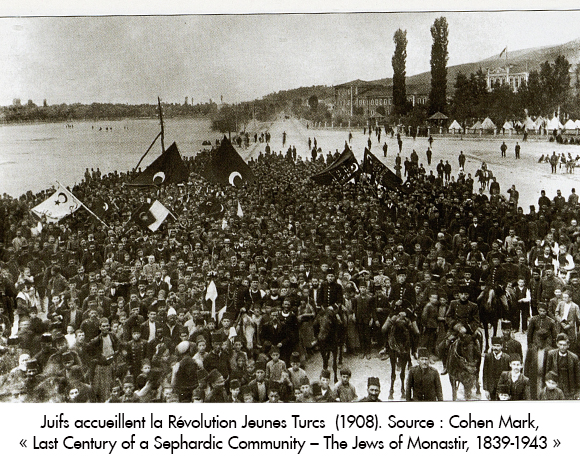

- Young TurkRevolutionand the Jews

The Jews welcomed with open arms the transition to constitutional monarchy which allowed them to have the same rights as the Muslims under the Ottoman Constitution. From a symbolic point of view, the presence of the signs in Hebrew testifies for the warm welcoming of the Jews.

On the other hand, the Revolution brought a series of questions, in particular on the language of instruction in the schools of the AIU. Monastir is not spared by this debate: Isaac Perez, a young teacher of Monastirian origin in Adrianople, highlights the internal conflict within the School Committee. He indicates that several members were opposed to the new director of the School and his demand of assigning more hours to the Turkish language than to the French language. Isaac Perez takes part in the debate by posing the question to the director of the AIU: “Is it necessary to partially suppress French in Alliance schools in favor of Turkish?” He shows his solidarity with the pro-Turkey members of the community and his conviction in the emancipation of the Jews in Turkey after the Revolution.

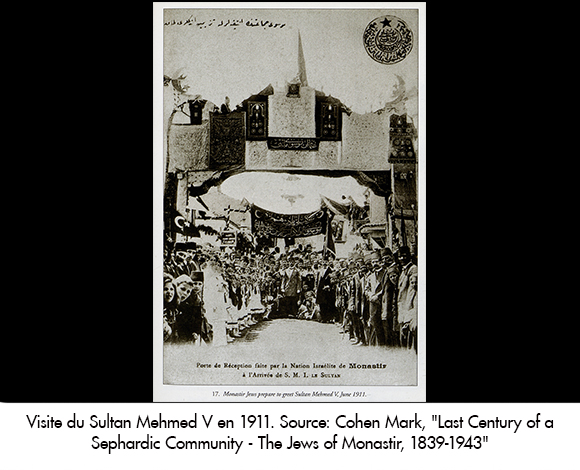

- Visit of Sultan Mehmed V

Mark Cohen suggests, in respect to Sultan Mehmed V’s visit to Monastir in 1911, that the Jews were more welcoming than the other communities and he mentions the triumphal arch built by the Jewish community as an example. It should be said that such a reception door is not built only by the Jews but also by the other monastirian communities. “Each nationality had a triumphal arch built around which they gathered themselves when the Sultan arrived” wrote Marie Benvenisté, the deposited director of the Girls’ School. She thus informs us of the obligation given to all the schools of Monastir to line up, forming a hedge for the monarch’s path.

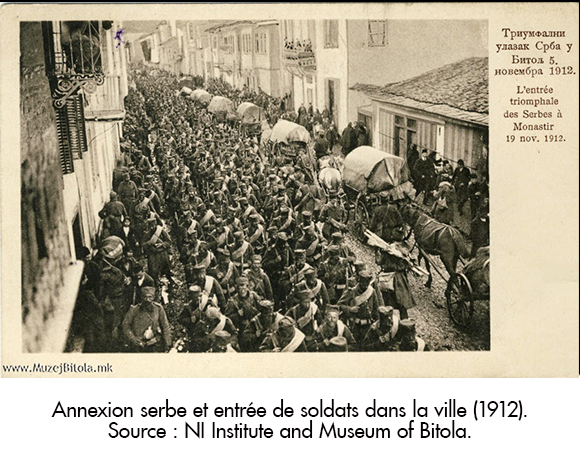

- Serbian annexation and new organization ofthecommunity life.

The end of the Ottoman regime brought a necessity for self-management of communities on the social, even legal level, due to the establishment of Serbian nationalist agents which only valued the teaching of the Serbian language in the country. The sponsorship of French diplomacy in favor of the works of the AIU revealed itself in that moment of trouble when all denominational schools were closed. Only those which were under the protection of France and Romania maintained their services. The hostile policy of the Serbian Kingdom towards denominational schools therefore did not apply to the AIU schools in Monastir and they could continue to operate.

On the other hand, the role played by the director of the Boys’ School, Joseph Bensimhon, in the reorganization of community life under the new regime is spectacular. He was part of the Monastirian delegation to welcome the Chief Rabbi of Serbia during his visit to Monastir in 1913.